EXTENDED BIOGRAPHY

Early life

Jaime Jackson was born on May 4th, 1947, in National City, California, and spent his early childhood in San Diego, where his family lived in post-World War II military housing. His father, a military veteran, was one of many who were provided with temporary government quarters while transitioning to civilian life. Located near both Mission Bay and the Pacific Ocean, Jackson’s childhood environment fostered a love for water activities.

He attended a rural school situated on the bay, where tidal waters sometimes flowed beneath the building. Following the end of the Korean War in 1953, his family relocated to the southern edge of Long Beach, where they settled near undeveloped farmland. This rural setting provided ample space for exploration and outdoor play during Jackson’s formative years.

In his youth, Jackson also had unique exposure to Native American culture. His father introduced him to American Indian elders involved in the creation of Disneyland’s Indian Village in Anaheim. These elders shared traditional skills, such as tipi-making and hide-tanning, which made a lasting impact on Jackson. He later accompanied his father on visits to reservations in the American Southwest, where he further learned about Native American traditions and languages.

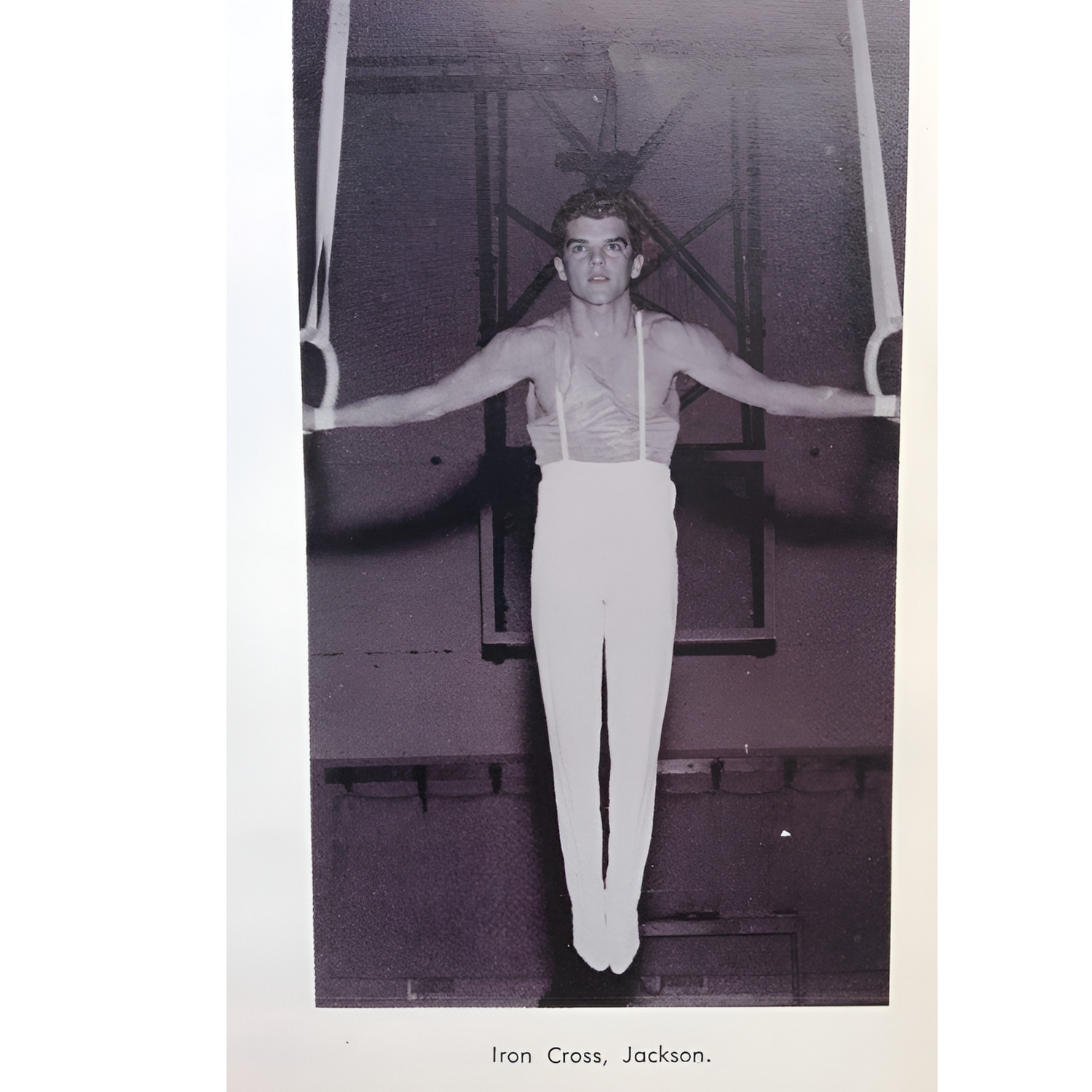

As a teenager, Jackson developed a knee condition that limited his participation in regular physical activities. He was enrolled in an orthopedic program where he engaged in weightlifting and strength training. This early focus on physical fitness led him to join his high school’s gymnastics team, where he excelled in competitive events, particularly on the rings. The experience instilled in him a lifelong commitment to physical well-being.

Jaime's academic journey involved several colleges, including the City College of San Francisco, where he pursued studies in subjects such as Shakespeare, Russian language, mathematics, and chemistry—the latter being his favorite. To support his education, he worked full-time during the summers and holidays at a local community hospital. It was here that his experiences inspired him to consider a career in medicine.

College and army

While living with his uncle in San Francisco, Jaime's academic plans took an unexpected turn when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in January 1968. With the encouragement of his uncle, he entered service, intending to resume his studies afterward with the goal of attending medical school at the University of California, San Francisco. On January 23, 1968, Jaime was inducted into the Army and sent to Ft. Lewis, Washington, for basic infantry training. During his induction, the Army recognized his educational background and future aspirations, offering him the opportunity to attend medical corpsman training at Ft. Sam Houston, Texas, upon completion of infantry training. Jaime accepted the offer and later completed training as an Operating Room Specialist.

While at Ft. Sam Houston, Jaime was exposed to the reality of the Vietnam War through casualties arriving at the hospital. He participated in operations for soldiers suffering from serious injuries, which deepened his understanding of the war’s impact. His advanced training continued at other stateside Army hospitals, where he assisted surgeons treating more war casualties, some of which were so severe that he began to question whether he wanted to pursue a civilian medical career.

In late March 1969, Jaime was deployed to the 121st Evacuation Hospital in South Korea, where he served until his honorable discharge in January 1970.

During his time in Korea, Jaime studied the origins of the Vietnam War, ultimately concluding that it was a grave mistake rooted in racism and war profiteering. His experiences in Korea, including witnessing the conflict along the Korean demilitarized zone, further solidified his growing anti-war sentiment. Upon his return to the United States, Jaime joined thousands of fellow veterans in the anti-war movement, dedicating himself to activism against what he viewed as unjust modern warfare.

Post army transition

After his discharge from the Army, Jaime became involved in anti-war demonstrations in the San Francisco Bay Area while continuing his studies in Chemistry. He briefly accepted a position at Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley but resigned after one day, as the job involved processing blood plasma for the Vietnam War. On January 23, 1973, coinciding with President Nixon's announcement of the war's end, Jaime found himself without a job and decided to move away from his initial career path.

Drawing on childhood visits to Native American reservations, Jaime set off on a motorcycle trip to explore California's reservations. His journey ended at a Pomo Indian reservation, where he learned about communes where people lived in tipis. Intrigued, he visited one and discovered that many Indians moved for better life opportunities. Inspired by the tipi's construction made with heavy canvas, he decided to start crafting them for others. He returned to the Bay Area to begin this new venture.

Sewing shop

After turning down job offers from two chemical companies in the San Francisco Bay Area, Jaime embarked on a new venture, establishing an industrial sewing company specializing in manufacturing products from heavy materials. Jaime pursued his interest in Plains Indian Tipis to form his new enterprise, heavy canvas tipis became one of the shop's core products.

Moving across the San Francisco Bay to Oakland, Jaime secured a rental space for his shop. A WWII veteran who managed the building took a keen interest in Jaime’s plans and introduced him to local garment industry professionals. Through these connections, Jaime acquired his first industrial sewing machine, which was generously gifted on the condition that he would remove it from the previous owner's premises.

He assembled a team made of a mix of young men and women, people he met during his college years and the anti-war movement. Several trips a year were made to the Sierra Nevada by another team of people that was formed to gather pine saplings from which tipi poles were made.

Jaime designed the majority of the shop's products, but he also taught himself to repair the industrial sewing machines. The team’s camaraderie grew quickly, and as the business grew a new name was chosen reflecting the primary product of the shop “Tipi Makers”. Local advertising garnered much sought attention, but a breakthrough came when the publisher of the renowned Whole Earth Access Catalogue and Whole Earth Epilogue discovered Jaime's Sewing Shop and included Tipi Makers in the Epilogue.

Versatility and openness to new projects continually expanded the scope of the business. The team handled everything from custom tent repairs to dog beds. Although tipis were the shop's primary focus, word soon spread about the shop’s ability to craft a variety of items from heavy fabrics. Within just a year, Tipi Makers had firmly established itself as a thriving business, laying the foundation for Jaime's future successes.

Among the shop's notable projects was the creation of a large tipi for American Indian inmates at San Quentin Prison. At the request of the prison warden, this tipi was made to commemorate the Native American Freedom of Religion Act in the 1970s. Additionally, Jaime’s team contributed to the American Freedom Train, constructing passageways for the train during the United States Bicentennial celebration. Jaime's work extended even further, undertaking projects as diverse as crafting covers for a U.S. government radioactivity detector on a military base.

Hide tanning

Jaime’s interest in hide tanning developed alongside his passion for making tipis, both of which were sparked by an early experience with American Indian culture. Captivated by discussions on tipi construction and traditional hide tanning led Jaime to eventually master the art of tanning hides in the traditional Native American way. Insights garnered from his experiences as a tanner were later published in his Buckskin Tanner book.

Jaime's tanning expertise was further refined through extensive research. He conducted significant studies at the Tanners Council Laboratory at the University of Cincinnati and the University of Oklahoma's Western Histories Collection. His research focused on the tanning techniques of Plains Indian bison hides, a topic with little existing historical documentation. At the Smithsonian Institution, Jaime unearthed a rare first-hand account from 19th-century ethnologist James Mooney, detailing the tanning practices of Cheyenne Indian women. Mooney’s notes included the tanning of 20 cow hides, which were used to create a tipi in 1903. Jaime later discovered that this very tipi was preserved at the Chicago Field Museum. He was granted the opportunity to inspect the artifact, which had been stored in an underground vault for over a century. This research culminated in Jaime tanning a bison hide using traditional methods, detailed in his book Cheyenne Tipi Notes, published 45 years later.

Throughout his career, Jaime tanned and sold over 700 hides, including those of deer, antelope, elk, and moose. In addition to hide tanning, he created traditional clothing adorned with colorful beadwork and porcupine quill embroidery, many of which found homes in museums and private collections. Jaime was also dedicated to passing on his knowledge, teaching others the craft of traditional tanning (to the right bison hide robe made by Jaime during Horse Trek).

The Canvas Tipi

The unique exposure to traditions of American culture would lead Jaime to preserve the knowledge he acquired on tipis inside his first publication. In 1982, Jaime published The Canvas Tipi, a guide to making and erecting canvas tipis, which also provided valuable information on sourcing raw materials. Though now out of print, this publication marked the beginning of Jaime’s contributions as a writer, and later, an author of many books in different genres.

Jaime’s interest in making tipis for others also extended to testing their durability and using them himself and at times with and for others. One winter in the early 70s, he made a small 9 foot high tipi and camped in the mountains of Montana. The tipi, partially under snow, but with a campfire inside, had an internal liner and ceiling called the ozan (Sioux), which also contributed to the warmth inside the tipi while deflecting the snow out of his living space. Visitors were invited inside and were impressed with the comfort of his tipi.

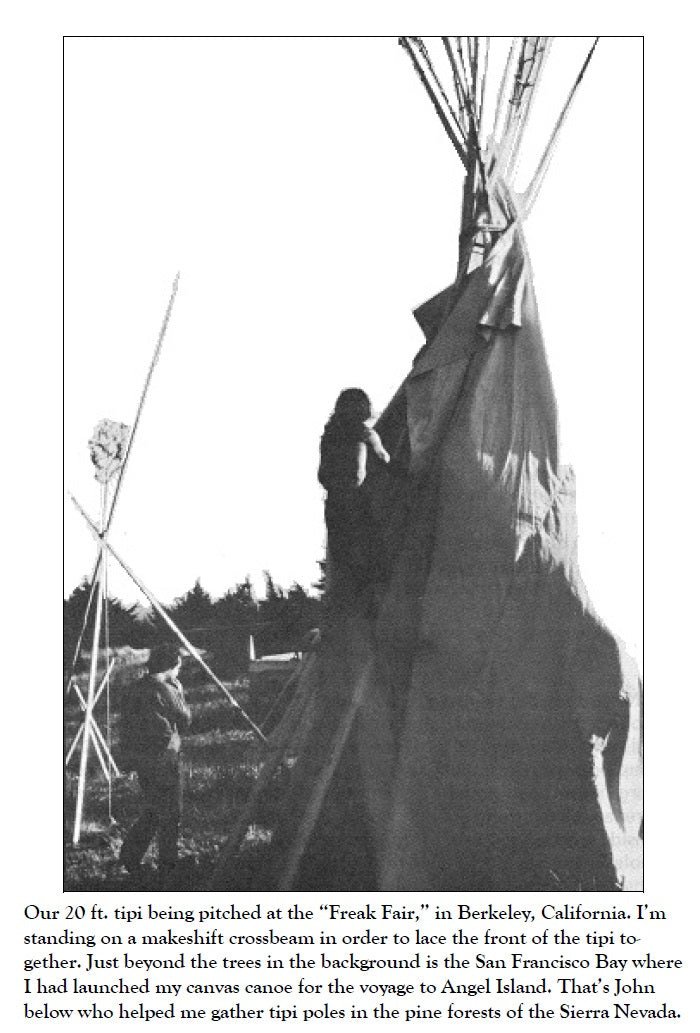

On another occasion, Jaime and his sewing team pitched and camped in a 21 foot high tipi during a special outdoor festival along the San Francisco Bay sponsored by the City of Berkeley. Thousands attended and most were introduced for the first time to the construction and use of an authentic tipi. One particularly memorable event occurred around the same time, when Jaime was invited by the warden of San Quentin State Prison to pitch a tipi inside a prison yard in celebration of the forthcoming American Indian Religious Freedom Act, attended by hundreds of Indian inmates. Jaime also pitched tipis of varying sizes around the Bay Area for other events.

The sewing shop and these experiences later inspired Jaime to write his first book in 1982, The Canvas Tipi, a guide to making and erecting canvas tipis, which also provided valuable information on sourcing raw materials. Though now out of print, this publication marked the beginning of Jaime’s contributions to preserving knowledge.

Horse Trek

In 1973, Jaime experienced a transformative vision that would define the trajectory of his life. This vision, which he later described in his book Horse Trek: Into the Mystic, depicted a dark, troubled world that would one day evolve into a brighter and more beautiful future. A horse featured prominently in the vision, an image that intrigued Jaime as he had no prior interest in or connection to horses. Jaime described this experience as profound as it marked the beginning of Jaime's journey into mysticism and what he came to view as his spiritual "Calling."

After sharing the details of the vision with two close friends, Jaime experienced a second vision on the same mountain peak. Although this vision did not include the horse, it reinforced his belief that he was being guided toward a new path. Convinced that his life was about to change, 1975 Jaime made a pivotal decision to sell his sewing shop and most of his possessions. Determined to uncover the deeper meaning of these experiences, he embarked on what he later described as a Vision Quest, a spiritual journey aimed at understanding its purpose.

Jaime's Vision Quest spanned nearly a decade and gradually brought him into a close relationship with horses. Remarkably, 1976 a horse resembling the one from his vision eventually entered his life, serving as a tangible symbol of his new path. This marked the beginning of his journey with horses and solidified the significance of the vision as a guiding force in his life.

Heeding the Calling, Jaime prepared for a long journey that would take him across the southern United States. 1976 He spent time learning to ride his new horse and gathering the supplies he would need for what he came to call the Horse Trek. 1976 his journey began in the forested bayous north of Mobile, Alabama, where he established his first camp before winter. During this period, Jaime also ventured into the coastal panhandle of western Florida, setting up temporary camps along the ocean.

Between 1976 and 1977 Jaime supported himself through tanning and leatherwork, crafting traditional items that he sold to those he met along the way. He supplied tanned hides and embroidered garments to an Indian trader from a Sioux reservation in South Dakota, deepening his connection to Native American traditions. These exchanges were not only a source of income but also a means of spiritual and cultural enrichment.

The natural environment played a significant role in Jaime's life during this time. His tanning camps along Chickasabouge Creek often attracted curious onlookers, including bayou alligators that nudged his tanning frames floating in the creeks. These encounters underscored the isolation and challenges of his chosen path.

As winter of 1977 gave way to spring, Jaime felt the Calling urging him northwestward. His path zigzagged through Alabama, Mississippi, and southern Arkansas. Along the way, he encountered a variety of people, most of whom were kind and welcoming. However, not all encounters were positive. One particularly harrowing experience occurred in 1977 as he passed through an enormous Ku Klux Klan rally in Alabama. Witnessing firsthand the racial tensions and lingering violence of the Civil Rights era left a lasting impression on him.

By the time Jaime reached the Ouachita Mountains late summer of 1977 in southern Arkansas, he recognized the need to prepare for the coming fall and winter. He continued to establish tanning camps come fall, eventually making his way north to the Boston Mountains in the Ozarks. Here, he found a cabin on a ridge top that served as his home for the next couple of years.

While wintering in the Boston Mountains (1977), Jaime continued to work with tanned hides and porcupine quills, creating intricate designs inspired by Sioux traditions. His skills as a craftsman gained recognition, and his work became a vital part of his life. As time passed (1977 79), Jaime was led to pursue a new career as a farrier. This marked the beginning of yet another chapter in his life, one that further deepened his bond with horses and his commitment to the path set before him.

Developing skills as a farrier

Jaime's path to becoming a farrier began during a pivotal long-distance horse trek—a formative experience that opened his eyes to the essential role of proper hoof care. Confronted with the responsibility of maintaining his horse's hooves, he sought guidance and mentorship from farriers he met along the way. Over the course of several years (1977-1982), while steadily building his own clientele, Jaime also committed himself to intensive training, laying a strong foundation for his professional practice. Jaime's journey into farriery began with his own horse. His sharp eye for detail and natural problem-solving ability helped him quickly gain confidence in the craft of horseshoeing. As word of his skill spread, more horse owners began to seek him out. Before long, Jaime was working full-time as a farrier while also pursuing his interest in traditional hide tanning.

Though Jaime’s reputation and career were steadily growing, he began to question the long-term impact of traditional horseshoeing—particularly the effects of nailing shoes onto a horse’s feet. Around 1977, a turning point came when a client gifted him a newly published book, Horseshoeing Theory and Hoof Care by Leslie Emery. In it, Emery proposed that the wild horse might offer a more natural model for hoof care, though he admitted he had never studied wild horse hooves firsthand. The concept struck a chord with Jaime. Moved by the possibilities, he reached out to Emery—an exchange that would mark the beginning of a lifelong collaboration, one that wove together practical experience and emerging theory in a shared mission to rethink hoof care from the ground up.

Jaime’s path into natural hoof care took a defining turn just a few years later (insert timeframe), when a wild horse—recently captured by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and made available for adoption—came into his care. The horse’s hooves were unlike anything Jaime had seen: strikingly unusual, yet remarkably well-formed. Fascinated by this natural perfection, he set out to understand its origins. That discovery led Jaime deep into the U.S. Great Basin, the rugged habitat of America’s wild, free-roaming horses. There, he began a hands-on study of wild horse hooves in their natural environment—an experience that would profoundly shape his philosophy and approach to hoof care.